Despite airs of child-friendliness, the actual built environment of suburbia is extremely hostile to children's most basic needs.

By Ryan McGreal

Published April 14, 2005

Our society makes a show of being child friendly, from playgrounds at fast food restaurants and furniture warehouses to the vast array of child-protection devices available to consumers. At the same time, our actual built environment is extremely hostile to children's most basic needs.

Richard Gilbert and Catherine O'Brien, writing for the Centre for Sustainable Transportation, have surveyed a huge body of research on how our built environment affects children, coming up with a list of 27 guidelines for creating safer, healthier communities.

According to Child- and Youth-Friendly Land-Use and Transport Planning Guidelines, children need fresh air, exercise, time to run and play, and a chance to move through neighbourhoods and interact with others. Instead, they are strapped into car seats and shuttled from destination to destination, missing exercise, breathing poisonous exhaust, and isolated from their communities. The low density development of "family friendly" subdivisions all but guarantees that parents must drive their children anywhere they need or want to go.

Children who do try to walk face automotive exhaust and the gauntlet of speeding cars if they want to get anywhere. The constant noise of traffic increases children's stress levels and the presence of cars forces children inside, where their opportunities to play and exercise are severely limited.

The results of sprawl development are clear: overweight children at higher lifetime risk of diabetes and heart disease, a significant increase in respiratory illness, even measurable effects on emotional development, concentration, and school performance.

These factors affect everyone's health, but children are especially susceptible, because their bodies are still developing and their lifestyle habits are still forming. Children also eat, drink, and breathe more by body weight than adults, increasing their rate of exposure to toxins.

Cars make low density development possible, and low density development requires cars. When buildings are spread out, distances between destinations are too far to walk and public transit systems can't operate efficiently. Further, the preponderance of cars on the road creates an unpleasant and unsafe environment for those people who do try to walk, further reinforcing car use.

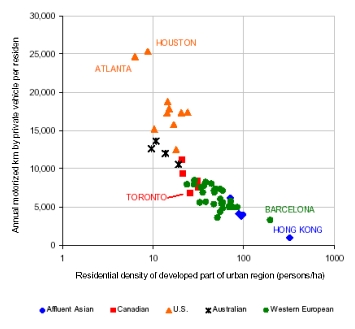

Car travel varies with residential density (note log scale for density)

Amazingly, as bad as air pollution is for pedestrians, Gilbert and O'Brien found that levels of air pollution inside vehicles are several times worse than levels outside vehicles. School buses, in particular, expose children to high levels of pollution from diesel engines. Children who sit inside vehicles instead of walking face the double whammy of lost exercise and sharply increased air pollution.

Aside from the environmental dangers to children, traffic collisions provide a much more direct and immediate danger. Crashes are the leading cause of injury and death in Canada for children older than one year. For all the understandable fear parents have of attacks and abductions, cars are much more risky than strangers.

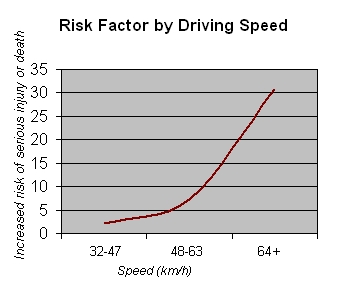

The risk of injury and death from traffic collisions increases exponentially with the speed of the cars.

The risk of

serious injury or death increases exponentially as vehicular speed increases (chart created based on data in the Report)

The authors' conclusion - and a recommendation that can be implemented immediately - is that speed limits in residential areas should be lowered to 25 km/h from the current 40 km/h. This would produce a number of simultaneous benefits:

Beyond this obvious step, the authors recommend a number of guidelines that support the development of a built environment that encourages pedestrian travel and provides safe streets for children to live and play. Their first guideline, "In transport and land-use planning, the needs of children and youth should receive as much priority as the needs of people of other ages and the requirements of business," leads naturally to the rest of the guidelines.

None of the guidelines state, "Communities should be built to a higher density", but few if any of these goals are possible where sprawl continues to dominate urban planning.

Here are the guidelines. In the report, each guideline is supplemented by a detailed explanation and examples.

Richard Gilbert and Catherine O'Brien, Child- and Youth-Friendly Land-Use and Transport Planning Guidelines, The Centre for Sustainable Transportation, March 28, 2005

By R (anonymous) | Posted September 16, 2006 at 08:14:39

Sir,

I came accross your article and wish to contribute that I have been planning and designing child friendly early childhood care centres, schools, playgrounds and urban parks, and a child-friendly/low-trafic childrens's avenue in Iran which are now under construction as well as child friendly schools, spaces, and environments in many countries in sub-Saharan Africa. Hence, Child Friendly Cities is a visionary concept which slowly-by-slowly is put into practice but perhaps not as fast in the Western world as you would wish. My advice....all it takes is to be patient, practical, and perseverant so, never give up.

All the best

R

You must be logged in to comment.

There are no upcoming events right now.

Why not post one?