If we want urban neighbourhoods to sustain commercial spaces that are also public goods, we need to explore quiet, incremental strategies for creative local reform without relying on either provincial or federal funding or hopes for a radical revolution.

By Loren King

Published April 04, 2018

The thing about being in a bookstore is that you find things that, yes, you could simply order online, but that you probably wouldn't think to order until you've encountered them. Local bookstores are a place to buy stuff, yes; but they're also a local site of exploration and discovery, and engagement with others interested in art and ideas and arguments and imagination.

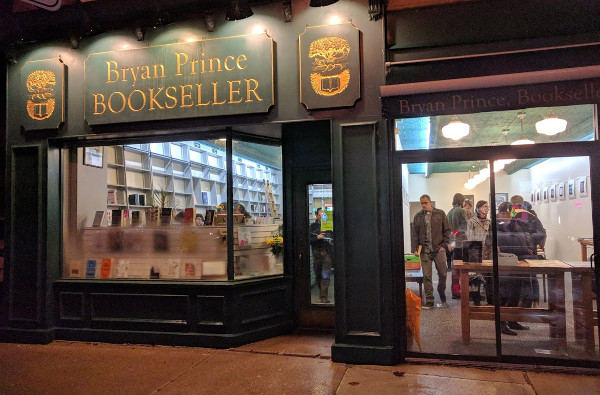

Bryan Prince Bookseller in Westdale (RTH file photo)

It's the local-ness I want to emphasize: it's important that these spaces of exploration and engagement be local: a part of the visceral, immediate lived experience of our everyday spaces.

Critics dismiss this "local exploration and engagement" as a conceit, merely an expensive taste enjoyed only by bookish urban elites. Those professors and hipsters, lawyers and doctors: they all talk this way, incessantly, but they still quietly order from Amazon and Indigo, Chapters and Coles while they top up the balance on their Starbucks app and drive in their hybrids or Teslas to the box stores to shop, so even they end up looking at the bottom line, right? Hypocrites.

That rebuttal isn't wrong, so far as it goes, but I think it misses something important.

Independent local bookstores, cafes, and the like provide vital public goods as well as their particular goods and services. Indeed, it's the way they provide their commercial services - in place, anchored in a neighbourhood - that generate the local public good in question.

It's reasonable to focus on the prices of their goods and services, yes, of course; but we should acknowledge that the local public goods they provide are valuable, and they won't provide themselves. Nor is it easy to provide them without their integral commercial component: that these things tend to coevolve together, organically, was one of Jane Jacobs' key insights.

But what to do? We've built our cities in ways that make it hard to provide these subtle but vital 'commercial public goods' for a great many people in the places they live. At the same time, the full costs of our mail-order and box-store choices tends to be obscured, then politicized by the likes of FordNation, who either don't seem to understand the concept of a public good, or simply refuse to acknowledge that they are in fact goods.

I'm not sure which is worse, but it's a politics of diffuse rage paired with dangerous ignorance or cynicism, or both.

It doesn't help that many of us who praise these local commercial spaces of exploration and engagement tend to be part of the disruptive processes of gentrification that make these kinds of spaces possible mostly only in the (expensive) places where we can afford them.

When urban ideals meet pragmatic concession, the result is often just the kind of complacency that makes an easy target for populist and critical rhetoric, on both the left and the right.

In this, at least, both the FordNation crowd and The Tower anarchists are on to something, and it's the same thing: the urban elite who sing the praises of bike lanes and Montessori daycares and green infrastructure live dramatically different (and much more expensive) lives than, say, new arrivals struggling to afford a house within a two-hour commute of their several jobs around the sprawling periphery of Toronto.

Or the precariously-employed single parent struggling to afford their dangerously dilapidated apartment on Barton Street, with a landlord trying to force them out so he can sell the entire block to a Toronto-based developer.

Solutions? I've pitched these groups before, and I'll do it again: the Hamilton Community Land Trust works to anchor the kinds of 'commercial public goods' I'm talking about, firmly in place, making local enterprises much less vulnerable to the vagaries of real estate speculation and rent-seeking.

And the 541 Eatery & Exchange is exploring a For-Benefit business model that falls somewhere between conventional profit-seeking enterprises and not-for-profit strategies of community-building and social support. I know I'm a bit of a broken record pushing these two Hamilton groups, but I think they exemplify the kinds of quiet, intensely local creativity we need.

I also know that these examples won't impress those who think anything short of revolution is simply kissing the ass of big capital and legitimizing their real estate thuggery. They also won't impress the FordNation crowd, but then, they're not interested in being persuaded of anything, and their leader is cynical enough to know that his support has nothing to do with facts or coherent policy proposals (as Ryan McGreal recently emphasized).

All of that said, Amazon and Starbucks aren't going away. Neither are real estate speculators who want to cash in on the promise of vibrant new urban spaces. And those angry suburban voters are also sticking around: they love the Ford Family spectacle and resent the very idea that public money might be used to provide public goods, especially for those obnoxious urban elites in their quaint Riverdale renos ("we went for all-green appliances!"), sampling artisan doughnuts on Locke Street during a day trip to Hamilton ("it's changed so much! have you tried the Art Crawl?").

If we want urban neighbourhoods to sustain commercial spaces that are also public goods, like Bryan Prince Bookseller, then we need to explore the kinds of quiet, incremental strategies for creative local reform of existing realities, without relying on either aggressive public provision with provincial or federal funding, or hopes for a radical revolution that cures the ills of capitalism.

And we want strategies that don't simply reinforce the mechanisms of exclusionary gentrification (which means Richard Florida, who at least now seems to recognize the problem, is still not especially helpful).

Community land trusts and For-Benefit enterprise models may be the best games in town.

By JasonL (registered) | Posted April 04, 2018 at 20:48:44

If Bryan Prince Books had never existed, but was proposed as the ground floor tenant in a new downtown condo building, all the wackos would be throwing rocks and neighbourhood groups would be screaming "gentrification" ..... we've lost a gem of a business, and have lost many more that never had the chance to exist because we've allowed our city to remain hallowed out, undeveloped and not friendly to business.

By CharlesBall (registered) | Posted April 05, 2018 at 13:42:58

Instead of funding just cut the taxes. Commercial tax rates in Hamilton are outrageous.

You must be logged in to comment.

There are no upcoming events right now.

Why not post one?