The recent vandalism on Locke Street, and the responses to it, are symptoms of the loss spaces and relationships that are not governed by market logics and gentrification.

By Simon Orpana

Published May 01, 2018

Whether baked or deep-fried, donuts provide a surprisingly apt symbol for the kinds of cultural and political tensions that accompany Hamilton's contemporary predicament as a steadily gentrifying "post-industrial" city.

Formerly common fare, an affordable, high-carb snack in the city that boasts the Tim Horton chains' first franchise location, donuts have recently entered the craft economy of locally-made micro-indulgences to boost the moral of a precariously employed but culturally astute "creative class" attempting to navigate the waning of the post World War Two society of industrial affluence.

At a time of mounting austerity and tightening mobility horizons, small businesses are making a virtue out of necessity, turning gourmet hamburgers into the new steak, craft beer into the new wine, and upmarket boutique donuts into the new ... donuts.

Perhaps it is this reduplication that has made donuts into a flashpoint for reactions and protest from the left as well as the right: unlike hamburgers and beer, which have become substitutes for markers of distinction that increasingly seem less accessible, expensive coffee and donuts replace only the cheaper, more common versions of themselves.

This slippage within signifiers seems to chafe in places that twenty-five dollar beer and burgers do not, and the popularity of such operations as Donut Monster that opened this spring on Locke Street seems to have hit a nerve in the subterranean threads that contribute to the warp and woof of Hamilton's social fabric.

First, Locke Street was vandalized by a black-clad band of self-styled "ungovernables," whom local media were quick to label as anarchists due to an Anarchist Book Fair that was happening that same weekend. Windows were smashed, with particular attention paid to the donut store, an upscale brunch restaurant, and a gourmet cupcake boutique.

Windows smashed at Donut Monster (RTH file photo)

The vandals were forced to flee before they could reach the Starbucks, three short blocks away, but the corporate giant was obviously not the prime recipient of the perpetrators' ire, or they would have started their action closer to the north end of the street.

Forced by strategic reasons to chose between a mega-corporation and locally owned small business, the vandals chose the later, even breaking the windows of the old Locke Street Meats building, the owners of which had been supplying provisions to working-class Hamiltonians for several generations.

One might be tempted to call this incident a small, premeditated "donut riot." It drew the attention of national media outlets as well as eliciting significant support from the community, who flocked to Locke Street to show their love for local business by buying more donuts, cupcakes, and eggs benny.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau even dropped by, when he was in town to talk with concerned steel workers about Donald Trump's latest threats to invoke steep trade tariffs, and bought a gourmet pastry.

True to the imperatives to resiliency and ingenuity that inform contemporary entrepreneurial culture, Donut Monster bakers made the "Lemonade Donut" to commemorate the smashing of their windows, a confection with shards of candied lemon to represent broken glass, illustrating the adage that, "when the world gives you lemons, make lemonade."

Make Lemonade Donut (Image Credit: Donut Monster)

What the ungovernables mainly achieved was to increase the amount of hype the new Locke Street businesses like Donut Monster were enjoying, at the cost of some new windows and plywood.

But all the buzz attracted the attention of further reactionaries, a few weeks later, when a "Patriot Walk" was organized by a number of far-right white supremacist groups who announced that they were going to march down Locke Street, buy some donuts and support the local businesses that had been vandalized.

In response to the white supremacists, a much larger group assembled at nearby Victoria Park under the banner of Hamilton Against Fascism.

However, the HAF protesters were prevented from confronting the Patriot Walk on Locke Street by Hamilton's police force, which steered the protest march away from the area.

The irony that Hamilton had mobilized a sizable portion of its police force in order to secure the Locke Street neighbourhood so that a handful of white supremacists could buy donuts was not lost on several social media commentators.

Most recently, the arrest of an individual from Hamilton's anarchist community, who has been charged with conspiracy in relation to the Locke Street vandalism and denied bail under questionable pretexts, has the hallmarks of a bad suspense novel where someone gets arrested while the actual culprit remains at large.

Blaming the Locke Street violence and its aftermath on one or more individuals might help allay moral panic and uphold the laws of private property, but such actions do not address the deeper social contradictions that have produced this series of reactive, symptomatic responses in the first place: gentrification remains alive and well in the Hammer.

The pastry at the epicenter of these events remains a strange but somehow fitting catalyst for this constellation of unrest. Stripped of all the gooey icing, sprinkles, and candied lemon shards of metaphorical glass, the foodstuff remains a piece of bread wrapped around an empty centre.

The series of actions and protests recently focusing on the Locke Street neighbourhood likewise resemble so many symptoms organized around absence and displacement.

If we remain at the surface of the matter, where all the culinary excitement and sprinkles reside, it would appear that the different agents involved are reacting to each other.

First the ungovernables threw some rocks, then the neighbourhood rallied around the damaged small businesses, then the white supremacists reacted to the ungovernables, and the antifa protesters reacted to the white supremacists.

And, just like premium pastries offer temporary relief for weary spirits, all the players involved got a kind of sugar rush out of their respective indulgences.

The ungovernables got to feel they are dealing a jab at the establishment they resent.

The white supremacists garnered public attention that helps compensate for their own precarious situation as the heirs of an embattled middle and working class.

The antifa protesters got to feel like renegade freedom fighters battling fascists.

And the Locke Street businesses got to feel that maybe four-dollar donuts actually do matter, if everyone is so upset or excited about them.

But what if all of these cobbled-together, reactive identities are simply shoring each other up, generating smoke and fury in order to cover over a constitutive absence that resides at the unrecognized epicenter of the entire assemblage?

What if, beneath the saccharine glaze of enticing donut toppings, such forms of acting out reveal a concealed blockage or absence, a deeper level of hunger that cannot be satiated by all the empty calories?

What if, at the centre of this whole confection is an erosion of the commons?

The very fact that such a proposition might seem opaque or awkward, alien or outlandish is testament to its plausibility. For the absence of open discourse over the loss of the commons is one of the missing coordinates that allows for the discussions about gentrification in Hamilton to remain largely relegated to the sidelines, even as the city itself undergoes seismic shifts that steer it towards becoming an overpriced suburb of Toronto.

More than a decade ago, when much of downtown Hamilton appeared to outsiders as a bombed-out shell unworthy of mention, but was attracting artists, families and investors who saw avenues into a space that offered markedly different opportunities than many other neighbouring urban centres, attempts to raise awareness about the threats of gentrification were all but shut down amidst a chorus of scorn and censure.

City boosters were miffed at what they perceived as a group of "outsiders" from the university (which is where some, but by no means all, of these critiques originated) intervening in the struggles of Hamilton to emerge from decades of obscurity and hardship.

Many of the same folks who dismissed the cautionary words of these early interventions went on to shape the cult of Hamilton that was emerging as artists and investors began devising ways to transform the city's humble, common character into marketable forms.

Ordinary, stigmatized "dirt" was transformed into marketable, fetishized "grit."

In subsequent years, as nascent street and art culture started to gain momentum, voices of concern and critique were similarly sidelined, but for different reasons: this was finally Hamilton's moment to shine after decades of obscurity and hardshipstruggle and stigmatization, and activists concerned about gentrification were dismissed as wanting to "keep Hamilton poor."

Now, more than a dozen years later, condo developers salivate over the city's plan to lift downtown height restrictions in an attempt to stoke land speculation; tenants across the lower city face increasing rents, low vacancy rates, and underhanded attempts from landlords to get them to move out so they can take advantage of higher rental points; long-time businesses close down due to higher overhead, to be replaced by glossy new restaurants and salons selling similar fare for twice the price; and the housing market is so hot as to cause bidding wars that dash many peoples' dreams of home ownership.

Now that gentrification seems a fait accompli, some of the same people who initially balked at discussing the problem are willing to admit it as such, provided nobody does anything to substantially impede gentrification's progression.

Could we identify this failure of discourse as possibly contributing to the kind of blockage and frustration that might lead a handful of angry, idealistic protesters to lob rocks through the windows of a purveyor of premium donuts? Psychoanalytically, the "passage to the act"-or "acting out"-occurs when avenues of symbolic representation become tangled, knotted or blocked.

Perhaps it is precisely the lack of a substantial discourse over the loss of the commons, a situation that entails a rising cost of living, the shrinking of diverse common and public spaces, mounting economic polarization, and crucial issues about our shared relationship to the land, that causes a mounting sense of discomfort and outrage to take pathological forms, like the destruction of private property related to upscale amenities.

I'm not excusing the vandals here: their allegiance to "ungovernability" seems actually to align them with the same market forces that are currently escaping governmental controls and rampantly restructuring the city for the worse.

What we need is actual, accountable government that does its job of looking after the public good, but this tends only to occur when people stand up and demand it. And breaking windows is not a step in this direction.

At the same time, the antifa group, which promises in its online publicity that, "wherever they [the white-supremacists] go, we go," does not get us any closer to the heart of these issues.

Just as the ungovernables helped boost the profile of the neighbourhood they were apparently attempting to damage and critique, so to do the antifa groups play into the logic of the racists, who actually require and draw strength from the kinds of reactive, public spectacles that some of us on the left seem only too happy to supply.

What distinguishes these contemporary "neo-fascists" from the older varieties they attempt to imitate, and constitutes their crucial weak spot, is the need they have for the outrage of others to shore up their own, deflated identities.

And uniting ungovernables, white-supremicists, and anti-fascists, in conjunction with the police forces often provoked, is the way the entire assemblage tends to reproduce the tensions, fears, and spectacular conflicts that reinforce a masculinist, violent intimidating and reactionary appropriatiion of public space.

At the heart of this donut, whose layers of frosting are now beginning to melt and blur into each other under, is the absent commons - or, rather, the eclipsed and obscured commons.

There is a great deal of writing and debate about the commons, the idea of which has its roots in the "common lands" that, in England and Wales allowed peasants and small farmers to eke out a living from shared lands whose use was governed by local relationships and agreements.

Between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, via a process known as "enclosure," the commons were privatized and given over to large landowners. This effectively removed the means of sustenance for a large numbers of people, forcing them to move to cities where they encountered new forms of poverty and alienation as factory workers.

Informed by this historical example, we can learn to recognize the commons in all those resources upon which people depend to live and flourish, but which cannot ever be fully contained by the strictures of private property, commoditization and relationships mediated by profit incentives.

Language, for example, is a variety of commons, as well as the air we breathe, and the kinds of sharing and support that sustain friendships, families, subcultures and political movements.

However, the last fifty years has seen the rise of an aggressive, global, market-oriented culture that tends to obscure the language, conceptual tools and historical acumen needed to publicly acknowledge the determinative role played by the commons in supporting and sustaining our lives and life-worlds, even while it attempts to "enclose" what remains of the commons via privatization and speculation.

In this context, the commons becomes a double negative: an obscurity which we only begin to perceive as it slips away under the pressures of unrestrained market forces.

But the common can't be completely absent, for if were so, we would be dead. Capitalism is a parasitic growth on the body of the common, a tumor that, as it grows bigger, threatens to kill the host body upon which it relies for its own sustenance.

It is for this reason that, as contradictions mount and election days loom, politicians often begin to sound like socialists, promising enhanced public goods with one hand while they sell off public amenities to make a fast buck with the other.

What gives this writer hope is the long history of practices of collective protest and commoning that constitute key elements of Hamilton's unique history, character and future potential. A triad of examples involving a dish, a clock and a steel plant will have to suffice here, though there are many more.

First, as is fitting in a discussion about donuts: the dish. One of the original peoples to be caretakers of the fertile lowlands along what are now Hamilton's desecrated industrial landscapes were the Attawondaron, a First Nations people whom the European settlers called the "Neutral Indians" because they refused to take sides with either the Huron or Iroquois during conflicts stoked by imperial interests.

Recognizing the great value of the land upon which lower Hamilton now sits, the Attawondaron related to their fellows under the Dish with One Spoon Wampum, an agreement that recognizes the area as a shared resource.

The Dish with One Spoon Wampum is remembered and celebrated by the people of the Six Nations to this day. It recognizes this particular land and place that sustains life as a single dish, our human relationship to which is mediated by a single utensil: not a knife, fork, or property deed, but a shared, common spoon.

The city of Hamilton thus occupies land that older residents recognized as a kind of commons: a resource that everyone agrees to find ways to use, but that nobody owns, because it is just too precious to leave to a single individual or group to manage.

Reorganizing space and resources by market forces, by contrast, does not constitute a commons since this is not an agreement but a structural imposition that presupposes and naturalizes key ideologies and relationships while actively blocking other possibilities. Under these conditions, the commons, when it appears at all, is likely to do so only in coopted and distorted forms.

For instance, one of the problems with Hamilton's new, flashy - and often very tasty! - food culture is its exclusivity. Not everyone can afford a three or four dollar donut, and the income margins that differentiate those who can from those who can't open a fissure down the middle of a kind of coffee-and-donut culture that used to be a hallmark of Hamilton's common culture.

As the city occupying this land continues to develop and flourish, we must struggle to find ways of honouring the Dish with One Spoon Wampum and the spirit of sharing, vulnerability, cooperation and inter-dependency that informs it.

Perhaps ungovernables, white supremacists, anti-fascists, and the establishments of Locke Street are dependent upon each other for more than just producing anxious spectacle; perhaps we need each others' energies, experiences and understandings to help build a more equitable, sustainable, diverse and livable city.

What would have happened if, instead of attempting to march angrily on Locke Street to confront the white supremacists, concerned activists showed up with free donuts and a willingness to try to understand the worldview of the people whom they cannot tolerate?

It is unlikely that such an exchange would magically resolve the ideological and social tensions between these groups, but it might have lead to a different outcome than the ineffectual theatrics that actually unfolded.

Moving on to the image of the clock, in 1872 in the midst of the flourishing of Hamilton's first wave of industrialization, workers formed the Nine-Hour Movement to fight for a shorter working week. The Saturday afternoons that these protesters laid down their tools to fight for were a bid for common time - an extra afternoon outside of waged labour that would allow workers and craftsmen time to educate themselves in their trades.

The nine-hour movement was a fight for a temporal commons waged by workers who did not want to overthrow capitalism, but engage more fully in it as master craftsmen and the owners of their own small industrial concerns. They are thus the predecessors to the current wave of entrepreneurs who, with the waning of the kind of cradle-to-grave employment offered by industrial capitalism, have rekindled the utopian hope, shared by the protesters of 1872, of being their own boss.

It is instructive, then, to remember what happened to these same Victorian journeymen and small manufacturers: they were largely bought up and assimilated by the emergent, monopolistic corporate capitalism that created companies like Stelco out of an amalgamation of smaller, individual enterprises.

In our current, information and service-oriented economy, with its attendant quirky restaurants, coffee shops and craft boutiques, a parallel move does not necessarily need to involve some big corporation, like Starbucks or Wal-Mart, muscling in on local merchants and choking them out. It is enough for the gentrification process to raise rents and property taxes, as well as the general costs of living, to such a degree that it becomes unprofitable for small businesses to stay in operation.

If it hasn't happened already, this is where the donut really starts to spoil. All the quirky, fun and exciting local businesses, arts and culture that cities like Hamilton celebrate as attracting the kinds of professional people who buy houses and pay property taxes cannot survive once the cost of living rises beyond a certain point.

Arts and culture need the commons to exist at all, both in terms of materials used (think here of the history of forms and techniques that artists draw from, or the culinary traditions that restaurateurs rely upon in creating their fare), but also in the form of a sustainable provision of the necessities of life, such as affordable, stable housing, time away from work, and spaces of recreation that are not saturated by the imperatives of profit and consumption.

Hamilton has historically had a reserve of such spaces and resources, due to the legacies of industrial capitalism that see such amenities as merely constituting the life-support systems necessary for the maintenance of a healthy work force. Such resources as schooling, housing, health care and recreation were at least partially shielded from the privatization, profit-motives and competition that attend marketization.

"Art is the New Steel" is a popular slogan celebrating Hamilton's recent cultural upswing, but arts and culture are also the lure that the City and investors banked upon on to draw new investors and homebuyers to Hamilton.

Now that real estate seems to be the "new steel," artists, small business and culture workers may find it increasingly difficult to make a comfortable living, especially if they rent their work or living spaces.

Indeed, artisans and craftspeople might discover, too late, that they are "vanishing mediators"-key agents who, once they have played their part in bringing about social and economic change, are largely disposable, vanishing like the commons that allowed them to briefly appear, now forced to move to other neighbourhoods and cities in less developed stages of gentrification.

But how can we fight against this in ways that don't involve being forced to take sides between breaking windows and buying donuts?

This brings to the steel mill, and our third example of how the practice of commoning resources is fundamentally entwined with the history of the space now called "Hamilton."

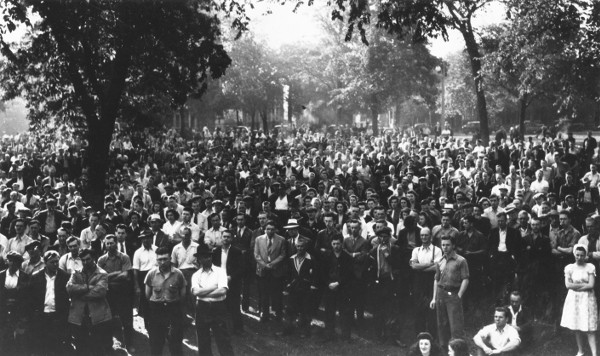

The multiple, mass strikes of the summer of 1946, which found their focal point at the gates of Stelco, Canada's largest steel maker, were essentially a battle over the recognition of industrial unionism: unions that represented, not just specific trades, but all the workers of a given factory or industry.

Union workers assembling at Woodlands Park (Image Credit: Workers' City)

Although the factories remained privately owned, winning the right to collective representation for workers was a pivotal part of the post World War Two society where ordinary people collectively demanded a better, more secure and stable life from government and industry.

In our current predicament, these legacies of predictable, stable livelihood and care often seem remote, but they constituted a form of commons fought for and won from an establishment that would rather have kept people in a more precarious and exploitative situation.

While we can't, and probably wouldn't want to, go back to this compromised formation (despite the unhelpful forms of nostalgia mobilized by recent, reactionary nationalisms), we can take from these events a memory of resistance and a cardinal lesson: progressive change only happens when enough people, from enough walks of life, stand and work together to make it so.

Hamilton is usually associated with a gritty, down-to-earth character associated with its twentieth century history of mass industry. But these industries would not have flourished were it not for the commons and practices of commoning on which they relied, often in a parasitic manner.

The easy access to cheap electricity from nearby Niagara Falls, proximity to waterways and rail lines, the availability of a diverse, skilled and eager workforce due to immigration, and the availability of cheap food from the surrounding green belt were all forms of commons that heavy industry relied upon, even while it steadily eroded and depleted the very environment that these same workers needed to live.

And this environment itself has a long history as a commons, from at least the time of the Dish with One Spoon Wampum. Remembering this history, which is still very much present despite the forms of rhetoric and ideology that attempt to obscure it, can help us navigate contemporary struggles to resist the kinds of displacement that gentrification produces.

It is not necessary, for instance, to make a forced choice between "keeping Hamilton poor" and embracing contemporary gentrification. In reality, the latter is not a remedy to poverty, but actually increases the gap between rich and poor. The displacement that gentrification causes does not lift people out of poverty, it merely forces them to move to other towns or neighbourhoods when they can no longer afford to live where they are.

When we add the memory and practices of commoning to this equation, however, we can pursue a third option that complicates the binary of poverty vs. gentrification, revealing the latter to be an ideological move designed to shut down discussion and corral our imaginations and desires.

People in Hamilton can provide and are providing organized protest and resistance to the forms of displacement that accompanies gentrification.

They are organizing tenants' rights groups to educate people as to their rights to safe, affordable and decent housing.

They are creating co-ops, collectives, and land trusts, and reinvigorating neighbourhood organizations as modes of realizing our shared stewardship of the city, and the strength and dignity we cultivate when we work with others to assert our common interests.

They are continuing the practices of mutual aid, hospitality and generosity that have characterized this area's culture for centuries.

They are framing informed critiques of the Downtown Secondary Plan, and have successfully fought for the inclusion of provisions that will allow the City to exert Section 37 of the of the Ontario Planning Act, legislation that other cities, like Cambridge, Ontario for instance, have used to their benefit.

Section 37 requires developers seeking to build beyond prescribed height limits to compensate the city by offering social amenities in return, such as public parks, low-income rental units, and day care centres.

Whether intentionally or not, Section 37 underscores that airspace, unobstructed views, and the city skyline constitute a form of commons, and development that impinges upon this must offer material compensation in the form of other common goods.

It is an instrument the can be used for the common stewardship of urban space, but only, it seems, if citizens stand up and demand that City Hall performs its civic duty in this regards.

All these practices tap into the long but often obscured history of commoning that has shaped the fertile lowlands along the southwestern tip of Lake Ontario. By keeping these memories alive, they might continue to steer our relationship with each other and the land into the future.

So, the next time someone tries to make you to choose between poverty and gentrification, throwing rocks at restaurants or throwing punches at racists, precarious contract work or unemployment, or any other forced choice between exclusionary binaries, remember two key traits of that most common of foodstuffs, the humble donut: being a continuous, tubular surface it really only has one side, and it's impossible to eat the hole.

Though the opinions expressed herein are the author's own, he would like to thank the several people who offered feedback, editing and formatting help with this essay.

By Eddy (registered) | Posted May 01, 2018 at 20:24:38

A lot of worthwhile things in this article. Too bad the writer jumped the shark and undermined himself by suggesting an answer to Nazis is not to counter-protest them but to buy them donuts and attempt to understand their ideology so we can all just come together and get along. Seriously?! Especially considering so much of the article was dedicated to historical examples of the power of people coming together to confront oppression and DEMAND change - not be passive and buy donuts for oppressors and attempt to empathize with why they are being oppressive.

I do not want to risk my safety hanging out with entitled, violent people and spending my precious time empathizing with Nazism. These organized Nazis violently assaulted people in our community away from press - they are not supreme gentlemen out on a peaceful walk/"Patriot March". And we already have a diverse city. Nazi's hate diversity. It's kind of their thing. You can't be on everyone's side unless you live in a fantasy world where people don't actually behave according to the ideology they subscribe to.

Suggesting that anti-fascists rely on Nazis so they have something to react to or to "be against" for the sake of being against something is ridiculous and completely ignores the history of the anti-facism movement both in modern terms and origins. There is no personal benefit from facing physical harm and confronting Nazi's - Charlottesville is a perfect example. Conflating Anti-Facists with Nazis is exactly what Trump did after Charlottesville. Booooo! For the people who actually show up to an counter-protest it's a hell of a personal risk and I'm grateful that people care enough to gather and show Nazis they aren't welcome in our community. Why not buy anti-protestors donuts for a change instead of criticizing them in a blog from a position of safety? I challenge the author of this article to rally a group of people to buy donuts for known white supremacist, groups converse with them about their ideologies, and then write an article about that experience. You can many of the groups on Facebook. Let us know how that goes. Keep it real. Peace!

By SimonO (registered) | Posted May 03, 2018 at 10:29:13

Thanks for your comments,Eddy. I realize that attempting to open discussion with people whose views are offensive seems difficult and even absurd, and yet I really do believe that these kinds of views are calculated to evoke just the kind of intolerant, gut reaction that mainstream society so often supplies. This kind of racism is a possibly unconscious but no less calculated form of protest, one cleverly designed to expose the forms of intolerance that secretly inform leftist politics, which likes to think of itself as tolerant but actually has significant blind spots in this regard. You mention privilege, but it doesn’t seem to me that the small groups who showed up for the “Patriot Walk” came from particularly advantaged backgrounds, at least judging by the photos that HAF took of them. I am inclined to read these conflicts as fed by unacknowledged issues of class, which get transposed into hyperbolic performances of all the signifiers that might disturb good, tolerant leftists. These strategies are pursued by people who have been left out of the kinds of politics that require the mobilizeation of specific, disadvantaged identities while leaving the larger issue of how the free market system exploits all of us unaddressed. It makes me sad to see this divide-and-conquor strategy reinforced by people on the left, who should be searching for ways to find a common cause that can shift the register in which the resentments and anxieties that beset us can be addressed.

In this regards, I take inspiration from the documentary, Accidental Couretsy, in which a black blues musician, Daryl Davis, explains how he has managed to collect the robes of over two hundred, now ex-KKK members. Davis befriends these former white supremacists one by one, using the history of music to open discussions about the ways white culture has historically appropriated and exploited black cultural forms. Music becomes the common culture that allows otherwise oppositionaly positioned people to find a way beyond the ignorance, fear, isolation and poverty that keeps racism alive. While Davis is an exceptional case, and we can’t and shouldn’t expect oppressed people to risk further victimization by interacting with intolerant bigots on this way, it does raise questions for me about how people who see themselves as allies might try different strategies for surmounting the impasses that our increasingly polarized society is facing.

The current dominant model of activism seems to involve silencing, shaming and casting out whatever folk devils appear, in an attempt to create a “safe space.” This, in turn, I see as a response the the shrinking of spaces of refuge and repair that processes like gentrification and the securitization of public spaces contribute to. It is a vicious circle, and the only way out is to take a step back and try to consider the bigger question of how market logics ultimately turn us into caged beasts who then start tearing at each other out of dispar and panic. What might seem like utopian dreaming to some, I see as an invitation to start heroically imagining, and working towards, a different world.

Comment edited by SimonO on 2018-05-03 10:33:18

You must be logged in to comment.

There are no upcoming events right now.

Why not post one?