Unlike flesh and blood people, forgetting about fictional characters is all it takes to make them go away. This difference can be a bad thing or a good thing, depending on the companion you've brought with you.

By Mark Fenton

Published May 31, 2016

What I tell you three times is true.

—Lewis Carroll

My grandmother has died. She was 103 years old, and her life and passing were enviable. She'd lived a full life and was alert and in little pain until the end.

Born into a world without computer games, movies or even radio, her great leisure enjoyment had been reading. And since early childhood she had learned poetry by rote, a skill that was then considered an asset to memory muscle and culture and was taught at school.

In her later years when she had time to herself, I often heard her recite now forgotten Victorian verse passages, some of which I suspect are lost forever as of today.

One favourite of hers that hasn't disappeared into the 21st century's sea of information is "The Owl and the Pussycat," a poem which I'm told she recited in its entirety a few days before she died. We hear a lot about the perils of memory loss as our brains age, but let's take a moment to consider the potential of human memory.

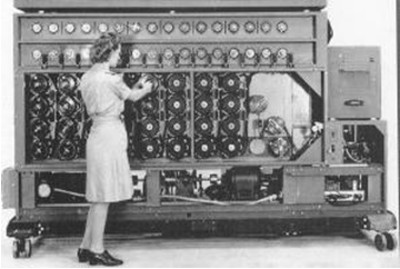

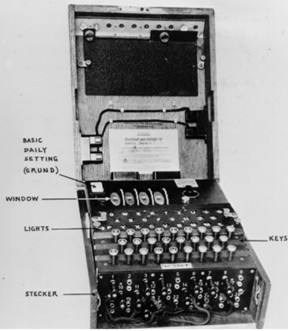

Assuming she learned this poem as a child, it might well have been preserved unaltered in her memory for 90 years. That's a whole lot longer than I've ever owned any laptop or phone or CD or workable memory stick. For that matter, she would have memorized this poem two decades before Alan Turing engineered the Bombe Machine

and cracked the code of the Enigma Box.

And still my grandmother was capable of opening her "Owl and the Pussy Cat" file, integral, as late as spring of 2016. In other words human cerebral matter stored a poem of reasonable length, longer than any digital retrieval system with significant memory has been around to be tested for durability.

"The Owl and the Pussycat" is an 1871 poem by the English nonsense poet Edward Lear. Here's what happens.

The animals in question decide to get married (more on this later). Rather than look at their joint finances and create a budget forecast for managing a household, they simply pool their stray cash and "[wrap it] up in a five pound note," a mind-bending metaphor for the Economics 101 definition of money as both "medium of exchange" and "store of value," as well as a prescient and self-recycling check on the environmental cost of wallet manufacture by making currency its own container.

They then jump in a boat and just drift for 366 days, or 367 days if it's a leap year since all we're told is it's a "year and a day" and there are no further temporal signposts in this - ahem - "poem."

The irresolvable impediment to the wedding contract is that they don't have a ring, though we're never told whether this is because there isn't enough cash wrapped up in the five pound note, or if they simply can't figure out where to buy one.

Finally they dock at the Intentional Community of their dreams, "the land where the bong tree grows." (Seriously?) Here they solve the nuptial challenge that has so far proven insurmountable by buying the nose-ring off a local swine for a mere shilling (i.e. they're the kind of liberals who celebrate diversity by sporting indigenous underpriced jewelry from exploited workers in places they never let you forget they've visited).

We leave them dancing the night away, blissfully happy - it's not stated but I think implied, from sucking back free hits off out of what appears to be a tree-trunk but is really the tube of a burbling bong.

So. To reiterate. This is the text that ran through my 103-year-old grandmother's last thoughts. Perhaps it's as meaningful a narrative as any for facing "that undiscovered country from whose bourn no traveler returns." (Google it if, unlike my grandmother, you've forgotten what you read in Grade 12 English class.) I hope she found in it a vision of heaven and not hell.

My struggle with the poem isn't so much the mindless hedonism that drives their journey, but rather how the narrative associates self-indulgent hippie slackers with what is pretty obviously a metaphor for "alternative" relationships, which as far as I'm concerned are just fine between consenting adults. In other words, it's the worst type of xenophobic conservatism that equates conjugal diversity with going on the dole and getting messed up on illegal substances.

Except that I do think we have to deal with a problem inherent in the relationship. Below the Subphyla "vertebrata" there is no biological overlap between domestic cats and owls. Now, I'm all for progressive ideas of who can be married to whom. (Incidentally, how this even "works" between Class 'Aves' and Class 'Mammalia' is something I've worked hard to imagine and am now working hard to unimagine.) And while some readers embedded in the 21st century zeitgeist will support inter-bio-class adoption, that's not the direction Lear goes with this, as we'll see later.

We can be sly at this point and say that 'Class' in the sense of taxonomic rank stands in for 'Class' in the sense of political hierarchy. This is, after all, a Victorian English poem sitting snugly in a tradition wherein class struggle is the very DNA of narrative. But Lear adamantly doesn't take it that direction either.

Again: this is the last poem my grandmother recited from memory. What I tell you three times is true.

I am not a religious person, and my family could be described as essentially secular. We're scattered across the country and there is no immediate plan for a memorial service. So I am on my own with the news of my grandmother's death. And I want to do something appropriate for the occasion, albeit something that doesn't involve getting in an open boat and sailing aimlessly away for a year and a day.

I recall lines from Philip Larkin, describing an impulsive visit to a church by a similarly secular person who later reflects on why he's done so.

...It pleases me to stand in silence here;

A serious house on serious earth it is,

In whose blent air all our compulsions meet,

Are recognized and robed as destinies.

And so out I go to locate a church. It is quiet and a weekday and I quickly find a marvelously peaceful block with a high density of sacred structures. A block delimited by Mulberry Street (South), Park Street (West), Colbourne Street (North), and MacNab Street (East).

Here I stand on the Park Street side where gargoyles cast a cold eye towards St Cyril's in front of which my camera can just make out a glowing statue of the Virgin Mary. A close crop

has her casting a caring eye downward and outward in contemplation. She appears to be blessing a car, but I assure you this is the ambiguity of camera angles and we'll soon have a truer and more reverent photo of her.

So transfixed was I by the stillness and the disparate elements of a block hermetically distinct from the blocks surrounding it, that I was startled to hear a voice asking me if I went to St. Mary's. (St. Mary's is the church just South of St. Cyril's.)

I turned to discover the man from whom the voice emanated. I replied that I didn't attend mass at St. Mary's. He asked if I was Catholic. I replied that, no, I was Protestant. As far as family heritage goes, that's accurate enough and I figured that this was the simplest answer to end his line of inquiry. I didn't think to say that my Grandmother was born into a more actively Protestant community than mine and that she had died today. And I don't know if I would have said that even if I'd thought of it.

The man asked me if I could spare some money. He gestured to his head and said he was trying to get a haircut (though I thought it looked less in need of cutting than mine). The man was speaking to me with the concentration of someone in the thick of the day's work that for him it was. I reached in my pocket and gave him the $2.50 I found there. He turned to leave and then turned back and asked if I didn't perhaps have some small bills. I said that I didn't. This was a lie.

I proceeded on my way and became uncomfortable with the lie almost immediately. I was, after all, standing before a serious house on serious earth. I turned to try and find him again. With the intention of giving him more money. And also, selfishly, of getting a photograph of the transaction. But he had disappeared from sight.

From there I moved to the epicenter of the block. (Technically I'm on a cul-de-sac called Sheaffe Street here and I'm standing at the exact centre of its turnaround bulb.) I took a 180 degree panoramic photo.

Then completed the circle facing eastward.

In the centre of this second semicircle and in roughly the centre of the block of church-related buildings stood a man with a metal detector

So far I had discovered two people here and two people only: one asking for money, the other searching for it. Churches are magnets for loss and impoverishment.

At this point I went and sat in the garden of St. Mary's.

I had chosen to bring Pim with me on my journey.

The strange comfort for the writer of fiction, a practice noted for its solitude, is the ability to bring characters along with us wherever we go. When we lack living companions there are always our creations, be they as silly as a betrothed beast and fowl, or in my case as absurd as Pim, the subject of a children's book I have finished and which I hope to have published soon and who, in the meantime, tweets daily @_PIM_SLIM_.

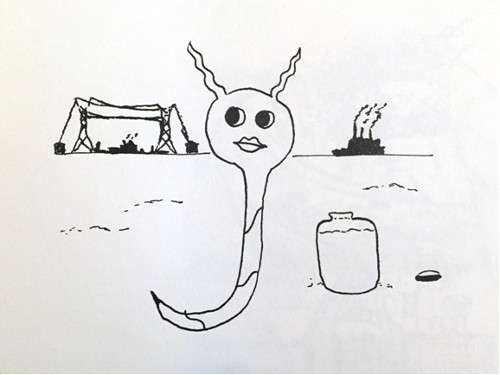

And the beauty of Pim is that when I can't find Pim, I simply draw Pim.

Pim's distinguishing feature is an even temper and a perpetually sunny outlook. This attitude can get on my nerves sometimes but mostly having Pim with me puts me in a good place.

Perhaps Pim's happiness stems from Pim's simplicity. A few lines and Pim is with me. And I wanted Pim's company, having just learned of my grandmother's death. Someone is lost, so one turns to someone else.

An aggravation of writing about Pim is the lack of non-gender-specific personal pronouns in English, and I cringe at the number of reader neurons I've already obliterated by typing 'Pim' like a mantra, since I can't accurately replace Pim with "him" or "her."

Unlike the owl and the pussy cat, who force on the childhood consciousness the possibility of reproduction between Aves and Mammalia, Pim is asexual. As long as you keep Pim in that jar of salt water (depicted above) Pim remains integral.

However...Leave Pim out for a few hours and Pim divides in half, creating Pim and Bim. Leave both out and they become Pim, Bim, Gim, and Zim. Leave Pim, Bim, Gi- You get the idea. Do the math. You'll want to take care with Pim. It's not like we need another environmental crisis.

And yes. Pim uses whatever gender of public washroom Pim chooses.

I sat in the garden for some time with Pim, allowing Pim to bounce freely around, and increasingly conscious of how the space around these churches formed itself into circles: garden centerpieces,

patio areas with benches surrounding them,

flower beds.

(There. See. She has no interest in the car, rather she's keen on the flora. And why shouldn't she be? If you've ever done day after day of 24/7 childcare anything you can look at while safely holding the baby is endlessly fascinating and just fine to do.)

Circles make sense for a serious house on serious ground. Circles comfort us. By geometric definition a circle has a centre, and when we are at a centre we are somewhere. No surprise that during the scientific revolutions of the Renaissance, a universe which did not place Earth at its centre was an unthinkable affront to the Church.

Personally, being at the centre of anything makes me feel anxious and trapped, like a self-sufficient organism in a jar. Fine for Pim. But I prefer the outskirts.

I headed Eastward. I was actually getting a little tired of Pim's good attitude at this point but Pim followed me and there was little I could do about it. We went past amusing objects. Objects upon, and under, and over, and through which Pim frolicked.

We passed alongside urbanscapes that said to us, "The universe has no centre whatsoever

unless you think a discarded easychair is a compelling focal point for life's mysteries."

We went past places where a battle was underway between nature and industry for dominion over the earth's surface. And it comforted me to find places where nature was taking back its birthright.

Pim bounced around me saying chipper things like "these are really delightful places you're taking us through. Although I'm always quite happy to stay in my jar." (Yes Pim talks. Further challenging my predilection for glum silence when I walk.)

Finally we came to one of the city's countless hidden passageways. I can't call them a network because they don't connect with each other or relate to each other in anything resembling a system. They are off all maps. They have been beaten and trodden by a mythic unidentifiable culture whose citizens I'll never meet. And I discover them only when Pim accompanies me.

I sometimes think they exist only in Hamilton and are part of what makes my Hamilton inherently magical.

Pim and I walked this path into undiscovered country. The objects glimpsed through the fence

seemed either to be pieces of obsolete Bombe Machines, or building blocks for a civilization humans might colonize elsewhere in a universe in which Earth is no more the centre than anything else.

By now Pim was all over the place. In fact, it was at this point that I noticed there were 16 of Pim and I made a mental note to get those things back in jars ASAP. My Grandmother begot 4 children who begot 8 grandchildren, who have so far begotten 11 great grandchildren. Equaling 24 people. But it took a century. Pim got to 16 in a matter of hours. Think about it.

This strange progeny took me back to Edward Lear. Lear wrote the unfinished draft of a sequel involving the children of the owl and the pussycat but abandoned it after a few tepid stanzas. From the fragment he left here's how those offspring turned out.

And so we're partly little beasts and partly little fowl,

The brothers of our family have feathers and they hoot,

While all the sisters dress in fur and have long tails to boot.

As I said, I have no problem with those two getting married, but I think it's irresponsible to pursue fertility clinics and in vitro fertilization options to the end of making mutants with no place in the world and whose characteristics are split even among siblings.

No wonder Lear abandoned this unwholesome yarn. It suits a John Wyndham-like genetic terror tale from the 1950s. But no children's book publisher is likely to touch anything this toxic and troubling.

"But Pim-siblings reproducing like wildfire, or the genetic mixing of wildly divergent biological species are merely the stuff of fantasy. These tales remind us that it's human nature to lament biological crises we have, rather than to give thanks for imaginable horrors we're spared of," was what Gim (or was it Lim) whispered in a faint voice at the base of my skull, right before the 16 creatures bouncing around my psyche split into 32 with a deafening POCK.

The path ended at Myler and Sanford,

where I looked back at the way we had travelled.

I didn't plan to return through it. I wasn't sure it would even be there if I tried to find it again.

I hadn't brought water on my journey and it was the first hot day of the year and I was in an almost hallucinatory state and had been for some time and this state grew suddenly more intense. I was very tired. I forgot about the Pim-siblings. And that meant there were no salt water jars to worry about after all.

Unlike flesh and blood people, forgetting about fictional characters is all it takes to make them go away. This difference can be a bad thing or a good thing, depending on the companion you've brought with you on your walk.

The building I stood before was gorgeous. But with the chainlink fence at my back I couldn't get the whole thing in a normal shot. So I again switched the machine to panorama and moved it upward. This made the building a swollen curved tower which would have earned me a fail as a perspective assignment for my Grade 10 drafting teacher.

Then suddenly Pim was back, though thankfully without siblings (whom I really hope aren't free-ranging over North Hamilton right now). Pim commented that a building like that would be extremely comfortable for Pim or Pim-siblings, and no doubt it would.

And now my naked eye moves up the building and up the pole at its summit and up up up into the monochrome mystery of a cloudless sky and this seems as good a place as any to leave my grandmother.

By AP (registered) | Posted June 01, 2016 at 05:15:28

A great adventure, tour and tribute. I read that owl and cat story just the other day. Oh my. Take care :)

You must be logged in to comment.

There are no upcoming events right now.

Why not post one?