Adapted from notes for a recent talk.

By Ryan McGreal

Published March 13, 2020

Old-fashioned Hamilton streetcar

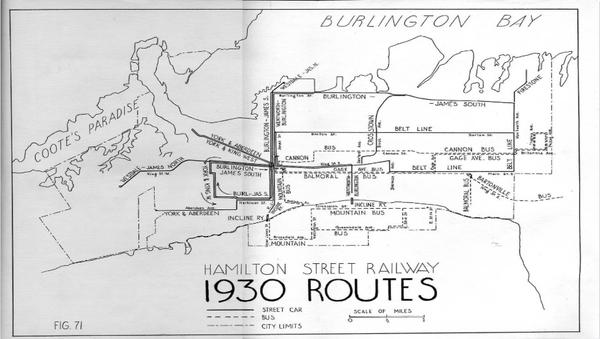

From 1874 until 1951, the Hamilton Street Railway was a network of actual street railways serving every part of the city.

At its peak, the network of electric rail transit lines was extraordinary, extending west to Dundas and Brantford, and east to Grimsby and Beamsville.

HSR route map, 1930

The Great Depression wasn't good to our street railways. By the 1930s, the network was mainly restricted to Hamilton proper, and those lines were not getting the maintenance they needed.

In 1946, after World War II, the HSR's owner, Ontario Hydro, sold the system to Canada Coach Lines, a bus company.

CCL decommissioned the streetcars and replaced them with electric trolleybuses, powered by overhead wires but running on rubber tires.

Electric trolleybus

Over time, the trolleybuses were also decommissioned for buses with internal combustion engines, and the last trolleybus line ended in 1994.

Meanwhile, in 1960, the City commissioned a study on transit planning that sounds like something a new urbanist would say today:

"If the downtown core of Hamilton is to continue to prosper, the use of automobiles will have to be restricted in the not too distant future. This in turn will require that transit facilities be greatly augmented."

They recommended serving downtown with "a subway or some form of rapid transit" - starting with an east-west line running between Westdale and Centennial Parkway, as well as north-south lines running on James Street and Ottawa Street from the north end to Mohawk Road.

A 1970 rapid transit feasibility study recommended moving forward, and the Province under then-premier Bill Davis was considering making Hamilton a test site for a new rapid transit technology.

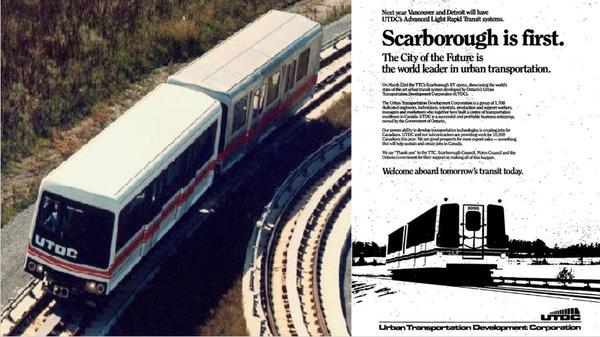

The Province launched a crown corporation called Urban Transportation Development Corp (UTDC), which proposed what they called an "Intermediate Capacity Transit System" (ICTS), a sort of halfway rapid transit option between buses and subways that ran on its own grade and used electric light rail vehicles. We would now call this modern LRT.

UTDC advertisement

They proposed to build a test system in Hamilton and pay almost the entire capital cost.

Detailed planning went into the design for Hamilton's system, which favoured a route circulating the downtown core and proceeding up the escarpment to Upper James and then east on Mohawk to Upper Wentworth, where it terminated at Lime Ridge Mall.

But this is Hamilton, and no transit investment proposal goes unpunished. A group calling itself "Coalition on Sensible Transit" (COST) formed to organize opposition to the plan, which had strong popular support (60% in 1980).

They used the tried-and-true misinformation tactics of Fear, Uncertainty and Doubt (FUD), warning about potential cost overruns, weak ridership and waves of crime and graffiti, insisting buses are good enough, proposing an endless variation of alternate technologies and routes, and so on.

Then-mayor Bill Powell called it "a system from nowhere to nowhere" as support for the system collapsed around the Council table.

The plan died in December 1981 when the Regional Government voted it down.

Meanwhile, the crown corporation that designed this new technology had more success in Vancouver, British Columbia, which built what would be the first in a whole network of LRT lines in its Skytrain system.

It seems fair to say the system Hamilton turned down has worked out pretty well for Vancouver.

Skytrain in Vancouver

That was the end of rapid transit in Hamilton until 2007, when the Ontario Government announced MoveOntario 2020, a 25-year rapid transit plan to try and play catch-up on more than a quarter-century of stagnation in rapid transit investment through the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area (GTHA).

Unlike previous plans, this new investment would be 100% capital funded by the Province through Metrolinx, a new crown agency created to implement the 25-year Regional Transportation Plan.

That plan included new LRT lines in Hamilton along the east-west B-Line corridor between McMaster University and Eastgate Square and along the north-south A-Line corridor on James Street and Upper James between the waterfront and Hamilton Airport.

Those would be the first two lines in a network of five rapid transit lines serving the entire city.

The City commissioned another Rapid Transit Feasibility Study and Council unanimously voted to approve the Provincial proposal.

Originally, the timeline suggested that the B-Line LRT would be completed in time for the 2015 Pan-Am Games.

LRT rendering

If you look carefully at this rendering, you can see a Blockbuster Video logo in the background. If you don't know what Blockbuster is, ask your parents.

The east-west B-Line was picked first because it's already ready for rapid transit:

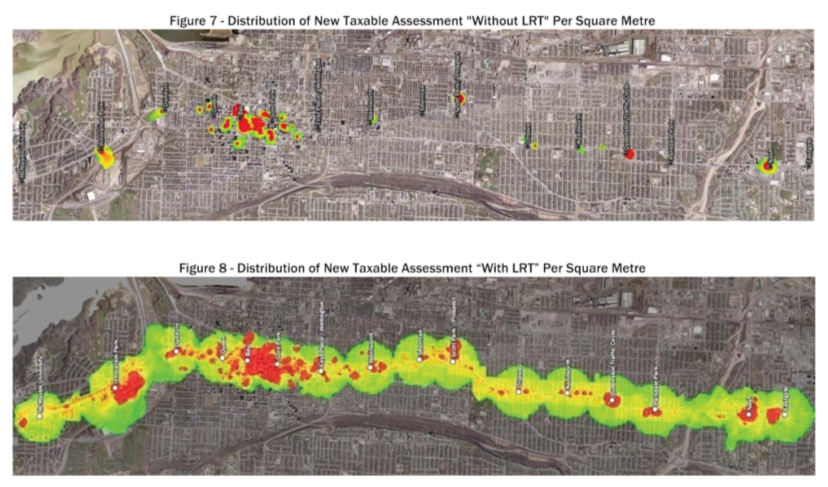

An early economic uplift study found that there would be more than three times as much new development along the corridor with LRT than without it.

CUI study: new assessment without or with LRT

And that analysis is almost certainly extremely conservative. Waterloo Region just built an LRT system that has already attracted $3 billion in new transit-oriented developments.

That kind of investment in Hamilton would add $70 million a year to our tax base - that works out to $270 a year per existing household.

A quick look at the map shows what that potential looks like. This is an overhead view of just the downtown core with vacant lots and surface parking highlighted in green.

But this is Hamilton, and no transit investment proposal goes unpunished.

The project development was delayed significantly in 2011 when then-mayor Bob Bratina started criticizing and undermining the project after running for election in 2010 in support of it.

He told then-Premier Dalton McGuinty that LRT was "not a priority" for Hamilton and suspended the project, diverting staff to other projects.

After a huge pushback from the public and supportive councillors, the project was eventually restarted but the LRT plan wasn't released until February 2013.

Bratina continued to undermine the project, insisting that the LRT plan was not really an LRT plan - prompting a heated argument with the City Manager in an April 2013 meeting and an Integrity Commissioner investigation.

At this time, the Ontario Liberals had a minority government and didn't know how they were going to pay for the next phase of Metrolinx projects, which included Hamilton LRT.

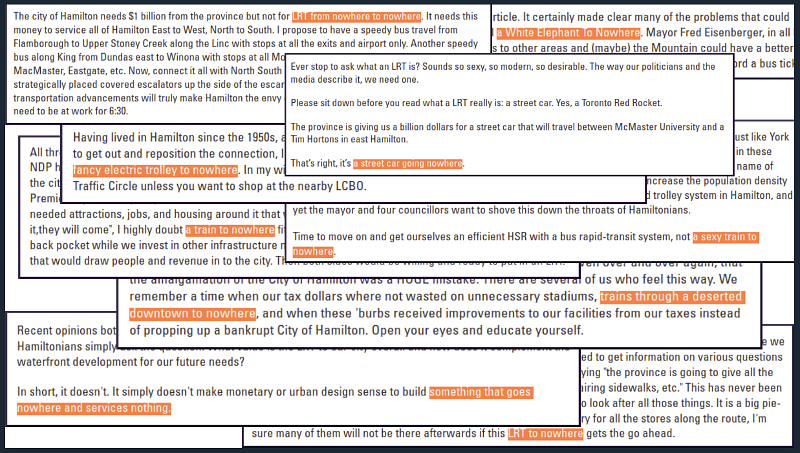

The project was in limbo, and the same old Fear, Uncertainty and Doubt emerged with a new anti-LRT group.

They used all the same fear tactics, warning about cost overruns, saying buses were good enough, insisting the route or technology was wrong, and most notably insisting that the system was "a train to nowhere."

Montage of letters to the editor

Indeed, the most notable factor in the anti-LRT group is that they seem to hold the city in contempt. One leader of the group actually delegated in front of Council and compared LRT to SARS and AIDS, two deadly infectious diseases.

The political failure in 1981 demonstrated the importance of not letting the naysayers control the narrative, and this time around there was a citizens group called Hamilton Light Rail that was dedicated to promoting the plan and challenging misinformation.

In the interest of disclosure, I was a founding member of HLR back in 2007 and am still actively involved.

We're Ready for LRT

We're not alone, either.

Hamilton Light Rail has partnered with an amazingly broad coalition of partners across the city to support LRT: the Chamber of Commerce, the Anchor Institutions - including Redeemer, Environment Hamilton, the District Labour Council, the Downtown and International Village BIAs, neighbourhood associations across the city, and hundreds of independent small businesses and organizations.

In 2014, the Ontario Liberals surprised everyone by winning a majority government, and in 2015 they confirmed approval and full funding for Hamilton LRT.

The idea was to conclude the Request for Proposals (RFP) process by early 2018 and get a contract signed so the project would be locked in.

Then City Council spent the next two years stalling and delaying, including waiting several months to approve an Environmental Assessment report and abruptly requesting to have the HSR operate the LRT line at the last minute.

The project was being procured using a Design-Build-Finance-Operate-Maintain (DBFOM) model, where the winning consortium would have to design, build and operate the system.

This is seen as creating an incentive to build it well, because shoddy construction means higher operating costs.

Council ended up not moving ahead with their proposal to have HSR operate the line, but the combination of all these antics is that the RFP was delayed by years and the LRT became a political issue again in the 2018 provincial election.

Progressive Conservative leader Doug Ford said he would listen to Hamiltonians on what to do with the money committed for LRT, and the NO LRT folks saw a golden opportunity to derail the project.

Sure enough, the PCs won a majority and the LRT football was kicked forward to the municipal election that October.

In August 2018, The Province directed Metrolinx to suspend the Hamilton LRT project and stop the purchase of 90 properties needed along the corridor to build the system.

Incumbent mayor Fred Eisenberger ran on his continued support for LRT, while a political operative named Vito Sgro ran a well-funded anti-LRT campaign that galvanized the No LRT movement.

Sgro's supporters turned that election into yet another referendum on LRT, squeezing out all the other important policy issues facing the city.

Once again, LRT advocates came together to counter the misinformation and support the project through this next hurdle.

Yes LRT lawn sign

In the end, Eisenberger was re-elected in a decisive majority across the enire city, winning 54% of the vote overall, as well as winning 13 out of 15 wards and 189 out of 222 polls.

In response, Premier Ford reiterated his support for Hamilton's LRT plan, saying of the Mayor, "If he wants an LRT, he's gonna get an LRT."

In March 2019, the Province lifted the hold on Metrolinx and the project resumed with full funding committed in the budget by the Treasury Board.

It looked like everything was going ahead until December, when Transport Minister Caroline Mulroney suddenly came to Hamilton to make an important announcement. The rumour was that she was going to cancel the project.

Minister Mulroney being evacuated by police

Local LRT supporters scrambled to get to the press conference. When the Minister saw the gathered citizens and councillors, she abruptly cancelled the press conference and actually called the police for an escort out of the building.

Mayor Eisenberger was left to announce the Province had cancelled the project after all, claiming that the cost had risen from $1 billion to an extraordinary $5.6 billion. It didn't take long to figure out that this new number was completely bogus. In fact, the Province's own independent cost analysis found that the project was still within the Treasury Board approved budget.

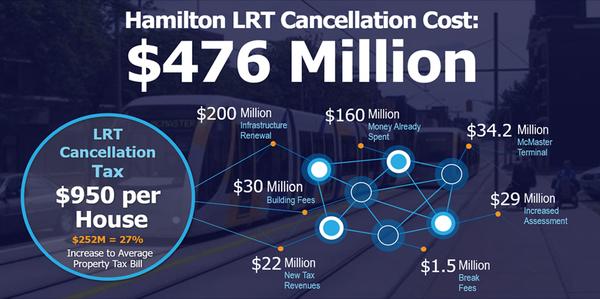

LRT cost cancellation

Metrolinx has already spent $184 million on the project. But there are also huge costs to Hamilton for cancelling the project. We're losing $200 million in direct infrastructure investment - including the Longwood Road Bridge, the Frid Street Extension and a new transit terminal at McMaster.

We're also losing the assessment growth. Again, Waterloo Region has attracted $3 billion in new development along their LRT corridor - equivalent to $70 million a year in property tax revenue.

We fall further behind other cities we're competing with to attract businesses and job growth.

And more of the new development we do get will be suburban expansion that costs a lot more to build and operate and generates less revenue per hectare.

Since then, the Province has convened a Hamilton Transportation Task Force that is meeting and is supposed to present its recommendations in mid-March.

Perhaps surprisingly, those recommendations might include reviving the LRT project. LRT still offers the biggest overall benefit to the city for the investment, and none of the underlying reasons for LRT have changed.

The Task Force is composed of people who understand this, and they may have been appointed to give the Province a face-saving way to reverse their decision.

Another controversial transportation project, Hamilton's Red Hill Valley Parkway, was first proposed in 1954. After decades of false starts, political fights, setbacks, lawsuits, resets, redesigns and protests, it was finally approved in 2004 and completed in 2007 - 53 years later.

It has now been 70 years since LRT was first proposed, so even by Red Hill standards, we're overdue to finish this project.

You must be logged in to comment.

There are no upcoming events right now.

Why not post one?