Chert is composed of microcrystalline quartz and has had two main uses: it was used by aboriginal peoples for tools and projectiles; and it has been used as a building stone.

By Gerard V. Middleton

Published May 06, 2013

Chert is composed of microcrystalline quartz (silica, SiO2) and in southern Ontario it generally occurs as nodules in limestone (Devonian, "Onondaga" Group) or dolomite (Silurian, "Ancaster chert beds" in the Lockport Group).

It has had two main uses: it was used by aboriginal peoples for tools and projectiles; and it has been used as a building stone.

In Ontario its use as a building stone was generally avoided, because it was not easily quarried in regular blocks, but has been revived by its use in large blocks for landscaping. Limestone or dolomite containing chert cannot be used for concrete aggregate.

This is an informal name given to a chert rich variety of the Silurian Lockport Group found at the crest of the Niagara escarpment.

Figure 1. Chert nodules (light grey) in the Ancaster Chert Beds, Sydenham Street, Dundas.

The nearest outcrops of Devonian limestones are found south of Hamilton, in quarries near Hagersville, but varieties in Devonian limestones of similar age can be seen in outcrops near the south shore of Lake Erie, from Fort Erie to Port Colborne.

They are often generally referred to as "Onondaga" but strictly speaking the lowest beds are older than the true Onondaga, and should be called Bois Blanc Formation. There were several quarries near Hagersville (most now flooded and all out of bounds to rock hounds), but the stone was crushed, and not used as a building stone.

For more details and pictures of Ontario cherts see knapper

Figure 2. Onondaga limestone with chert, Hagersville (scale in cms).

The origin of the chert in both of these examples was probably quite similar. Silica was originally extracted from seawater by sponges, where it formed fine "spicules" composed of amorphous silica. This form of silica was quite easily dissolved after burial within carbonate mud, and was redeposited in nodules composed almost entirely of silica.

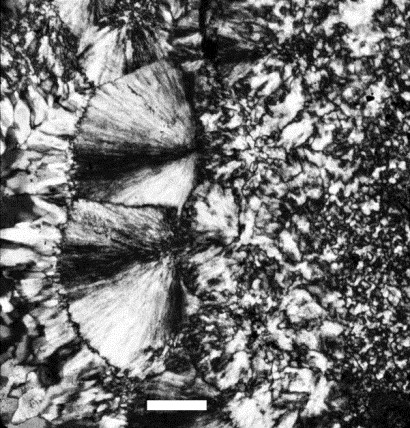

The process is quite complicated, but the result was generally a nodule (or a fossil replacement) composed of a mixture of microcrystalline quartz and chalcedony (see Figure 3). This is the common variety of chert, a term which also includes other, more spectacular varieties such as flint (by definition, the variety found in chalk), agate and jasper.

Chert is much harder than limestone or dolomite, and tends to break with a conchoidal fracture, leaving sharp edges - hence its use for making tools and weapons. For further information see Definition.

Chert is also important geologically, because it is formed soon after burial and often preserves fossils that would otherwise be destroyed by later alteration. For example, many of the earliest (bacterial) forms of life are known only because they were preserved in Precambrian cherts.

Figure 3: A micrograph of chert, showing both microcrystalline and fibrous textures. Mineralogically both are varieties of quartz, but the fibrous variety is commonly called chalcedony. Scale bar is 0.1 mm. Photo by L. Paul Knauth.

Archeologists use the generic term "lithic artifacts" to describe the various types of tools and weapons made from chert by aboriginal peoples, and they have developed sophisticated methods to classify the form of the artifact, and to determine the date at which it was made.

In southern Ontario the dates were mainly from the time of the last melting of the ice sheets, about 10,000 years ago, until the use of stone was replaced by metal.

Figure 4. Part of a map showing the sources of chert used for aboriginal tools. Note the sites south of Ancaster and along the northeastern shore of Lake Erie. From Fox.

Further information on the variety of cherts used, and an extensive bibliography are given by Fox.

As far as I know, none of the local cherts were used to construct millstones, though local cherts were used for this purpose in Ohio and Pennsylvania (Hannibal and others, 2011, Early Industrial Geology of Western Pennsylvania and eastern Ohio). Ontario mills seem to have preferred to use chert segments (buhrstones) imported from the famous quarries of La Ferté-sous-Jouarre, near Paris, France.

Figure 5: One of the quarries at La Ferté, near Paris, photographed about the end of the 19th century.

The buhrstones are early Tertiary (Oligocene) in age and are interbedded in grey or reddish shale. They were exploited at least since the mid 18th century and as many as 26 quarries were opened. In the 19th century some 3000 workers were employed in the millstone trade.

Many millstones were constructed from a single block of chert, but for foreign trade the chert was exported in segments, which can be seem in Figures 6 and 7. These were known as "English millstones".

I have found three candidates near Hamilton for millstones that used French chert. If readers know of any others, please let me know.

Figure 6: Millstone at the Snowball mill in St. George, Ontario. Note its construction from segments of chert, probably imported from France (it has now been broken into several parts).

Figure 7: Millstone mounted outside the museum in Brantford. The original mill has been demolished.

The third example is in Grimsby, Ontario. For more pictures see my GerryV2.

Chert was long used for building in England, in the form of flints weathered out of the Chalk formation (Cretaceous) known most famously for forming the white cliffs of Dover. For examples see flint.

In England, flint could be easily separated from the chalk, but in Ontario the local Silurian and Devonian cherts were not easily extracted from their dolomite or limestone host rocks, and could be used only for rubblestone.

The following are a few examples that used the Ancaster Chert beds.

Figure 8. This house, Glenhead on Scenic Drive, built in the late 19th century, Hamilton Mountain, is perhaps the best example of the use of Ancaster chert beds, quarried only a few yards away.

Figure 9. Detail of Glenhead, showing chert nodules (grey) in the dolomite matrix (brown). The irregular, mottled texture resulted from burrowing by animals during deposition of the siliceous muds (bioturbation).

Other houses on the Mountain that made use of the local cherty dolomites included the coach house at Auchmar (the main house was built of wood), and the Gate House on Garth Street.

The front part of the Gate House was built in the mid 19th century at the entrance to the Balfour estate, the rear is a late 19th century addition built from Eramosa dolomite.

Figure 10. Detail of the rubble stone in the front part of the Gatehouse. Note lighter coloured chert in brown dolomite. Scale in cms.

Hardly any houses that used the Cherty limestones of the Devonian can be found near Hagersville, although there are several quarries nearby (I described these in the first paper I ever published, in 1958; but the quarried are now all flooded and inaccessible). The best example is not even a real house but a farm shed.

Figure 11. Farm shed at Springvale, near Hagersville, built from a mixture of basal Devonian cherty limestone and sandstone.

More extensive use of Devonian cherts took place in Fort Erie, where the Bois Blanc Formation was particularly rich in chert. Similar stone can be seen in a few buildings in Buffalo, e.g. St. Stanislaus Church.

Figure 12. Chert (dark grey) in fine grained Devonian limestone at Fort Erie. Photo provided by Joe Hannibal. The present Fort is a reconstruction dating from 1937-1939, of the fort as it was before it was destroyed by the American in 1814. That fort was built from 1803 to 1813, and was preceded by earlier ones dating back to 1764. The stone is described in the official website as 'Onondaga Flintstone', i.e., the local Bois Blanc Formation.

Figure 13. St Paul's Church, Fort Erie. Built of much the same stone as the (reconstructed) fort. There are also a course and trim (windows, doors, buttress caps) of "Queenston stone". It was built in 1874 (? The first service was in 1881) replacing a wooden church built in the early 1820s. The church was destroyed by fire on Ash Wednesday, 1892, but rebuilt soon after. According to the Fort Erie website, some of the stone from the ruined Fort was used to build St. Paul's.

At Port Colborne, near the exit of the Welland canal, there is a stone house built from locally quarried Devonian cherty limestone.

Figure 14. The Lockkeeper's House, 44 King Street, Port Colborne, was built by David Price, stonemason in 1835, and later sold by W.K. Merritt for £30. It is a fine, if simple, two story Georgian house constructed of rubblestone, consisting of blocks of white limestone with abundant dark grey chert, which was certainly quarried locally from the Devonian Bois Blanc Formation. The history is thoroughly documented in the book by David G. Anger, 2006, Port Colborne: Tales from 'The Age of Sail'. Note: the 'not for sale' sign seems unusual to me!

Since Ontario began on a major expansion of its highways, and building in stone gave way to building in concrete, the demand for crushed carbonates (limestone of dolomite) has far surpassed that for building stone.

But one component of local carbonates that must NOT be present is chert. The chert (silica) reacts with alkalis in cement or asphalt to weaken the resulting product, producing cracks and popouts.

Much of the Lockport dolomite (Gasport or Eramosa) is relatively free from chert, but to reach the Gasport in quarries it is often necessary to strip away the overlying chert bearing beds.

At some time in the 20th century, quarry managers realized that, if they stripped away the cherty beds in large (metre-sized) blocks, they could be sold to the landscaping contractors. The blocks are not inexpensive, but cheaper than a stone dry wall. So now, you can see them everywhere!

Figure 15: Blocks of Ancaster chert beds, used for landscaping.

By Rimshot (anonymous) | Posted May 08, 2013 at 13:05:19

"If I could turn back time/If I could find a way..."

By Laurea (anonymous) | Posted May 08, 2013 at 18:43:31

I hope there is some Chert in Rockwood Ontario. James Dick Construction wants to blast a quarry in right on highway 7 and 6th line. There's wildlife to be considered, not to mention the water supply, the dust, the noise and the pollution (and excess traffic) from their trucks. CRC Rockwood. Concerned Residents Coalition is fighting this quarry. Join us. http://www.hiddenquarry.ca

You must be logged in to comment.

There are no upcoming events right now.

Why not post one?