Almost nobody but tenants in rental housing and the homeless in their camps actually feels the need for their right to housing to be met - affordable, secure, adequately sized and located housing, that is.

By Shawn Selway

Published March 06, 2020

York Street after widening. Source: Hamilton Spectator, November 1976, Hamilton Public Library Special Collections

As early as 1957, the Hamilton Downtown Association recognized the potential which federal urban renewal dollars could offer a city wanting drastic change. Hamilton's businessmen began to lobby for an urban renewal study to be carried out as required under the National Housing Act. They believed. that the money Hamilton spent on urban renewal would be regained through increased tax revenues due to the modern buildings' higher assessments and the fact that the services for development were already in place. They were convinced that they could fight the allure of the malls of suburbia by bringing pedestrian shopping centres into the urban inner core. (Rockwell, 104)

Over the next decade, this appetite for drastic change led to the destruction of houses in the North End and elsewhere, a vast downtown demolition and reconstruction program that crashed twice, put half of the long established concerns out of business and left large empty lots for years. (Rockwell, 110). It also entailed the total reconstruction of York Street.

The reason that the city needed to destroy the street, the planner Murray V. Jones told the Ontario Municipal Board at its hearings in April 1974, was "to meet traffic demands of the future." He told the board that he had originally chosen to widen York St. back in 1964 because "of its historic and functional role as an exit and entry to and from the city.' The street was going to have to succumb because the modernist need to create efficient transportation corridors was considered more important than the citizens who lived along the streets. The Barton Street freeway which had seemed so essential in 1964 was cancelled in 1970 because of the cut backs in federal urban renewal funds and the realization that the city couldn't destroy hundreds of homes. The perimeter road along Strachan Avenue in the North End [100 houses removed] was still expected to be built and would be linked to the York street freeway. [This road stayed on the books until 2012; even then, the Chamber of Commerce objected to its removal from the area's plan.]

The opposing voices had their say during the eight days of OMB hearings in April 1974... An NDP brief suggested that the city wanted to build the expressway "to woo commercial development to the civic square" and didn't want low income people living along the route to their prestigious development... However the city's decision to make York St. into an essential western link in the cross-town street system prevailed. The Ontario cabinet upheld the OMB decision and the Spectator wrote that it was too late for the city to turn back...

The city expected to destroy 249 properties and relocate approximately 500 families. Some people refused to move. Harry Mitsui who operated an upholstery business and lived above his store had to be physically removed by police. They handcuffed him and carried him out of his house in red boxer shorts with a blanket over his head to the police cruiser. His house was destroyed in 1976. "I went to jail for five days on a matter of principle," remembered Mitsui, "because I was fighting to stay in a home I lived and worked in for 28 years." (Rockwell, 131)

The urban renewal campaigns, particularly in the downtown, have left the city centre looking very bare today, especially when one considers how old Hamilton is and how prosperous it was for so many decades. The central city should be a dense, varied and layered landscape - and indeed it was; but much of the core was simply bulldozed during the sixties and seventies.

Ten years after the widening of York street, there were new buildings in the corridor. Forty-five years later there are a few more, but nothing at all comparable to the historical density of the mid-twentieth century has appeared and the "pedestrian realm" remains very underpopulated.

The obvious comparison is with James North, which in 1975 very much resembled York Street before its destruction. Because James was "left behind" its commercial life continued to evolve and the ebb and flow of investment was on a much smaller scale. Particularly in the last ten years, those flows and the turnovers that result have become more rapid.

But they occur one or two buildings at a time, that is, in small increments within a more stable context, without the wholesale destruction wrought by grand plans imposed by experts enacting the ideology of the day. This does not mean that the outcome of incremental change is necessarily the most desirable. Personally I find James North's steady conversion to restaurant row regrettable, but perhaps the new condo dwellers on the street would not agree.

The churn on James North. Two new restaurants coming soon. February 2020.

However, council's love for the Big Fix is a deep and lasting love, as shown most recently by projects like the stadium build, the LRT, and the current proposal to re-raze the core that was already flattened and trucked away fifty years ago - probably because the bigger the project the better the chance of pulling in provincial or federal money to supplement city resources insufficient to do the job. Insufficient also to heal the wounds when the outside funding is withdrawn.

But at least this time the momentum has been interrupted before the demolitions have occurred, so that Metrolinx has been left with a large stock of buildings, and under-developed or vacant lots. However, the structures are now boarded up and undergoing demolition by dereliction in the time-honoured Hamilton way, which usually leads in short order to a vacant lot that remains so for a very long time.

We have seen this at Queen and King, on James and Jackson where the site of the former Baptist church looks like the building was felled by a missile, and others. Some of these desolated areas are quite large - the greater part of the downtown block bounded by James, King, Main and Hughson for example; or the Barton Tiffany precinct which got the bulldozer treatment in the fall of 2011.

Thirteen houses were removed from Barton and Tiffany streets, and the premises of seven businesses including relatively new buildings housing a gas station/variety store and an auto-repair shop. An older industrial building in the centre of the Caroline-Hess block was also taken down.

Last to be demolished was a large structure with two huge interior volumes which might well be functioning today as a film studio were councillors less dedicated to making rubble and more willing to entertain adaptive reuse. Eight years on, this area is an unofficial construction waste dump.

Meanwhile, the Tivoli and 18-28 King at the Gore, ostensibly rescued from the wreckers, continue to sit empty, unused and unmaintained while the owners wait for their competitors to increase the land values.

Those small apartment buildings along King and Main are fine examples of the Missing Middle, the term which has become a catch-all for many types of "ground-oriented housing": row houses, townhouses, apartments in buildings under five storeys, apartments in duplexes, and residential units above commercial.

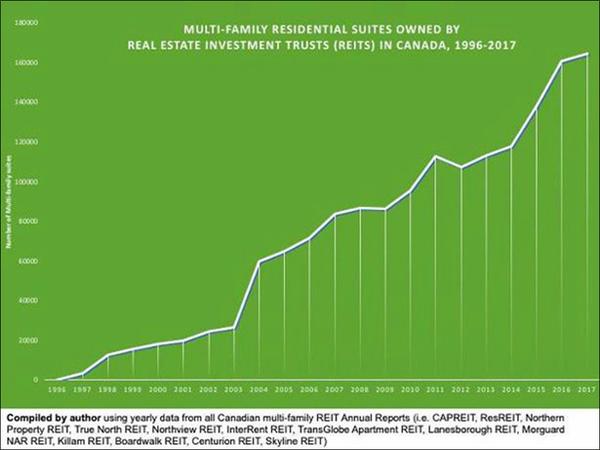

Demolition of these buildings would be doubly wasteful and harmful because it reduces still further the amount of rental housing available outside the high-rises, and those larger multi-residential buildings are now mostly in the hands of REITs dedicated to more or less ruthless programs of repositioning their assets in the market.

Middle range "ground-oriented" housing on King.

Mid-range on Wilson in East Central Hamilton.

The Missing Middle has been much discussed over the last couple of years and is the new darling of intensification proponents. It is "gentle density", so called to distinguish it from tall buildings which can land pretty hard if not subject to strict built form guidelines that enforce minimum separation and maximum heights, as well as a unit mix ratio that avoids the endless proliferation of monocultural barracks for singles and their canine companions.

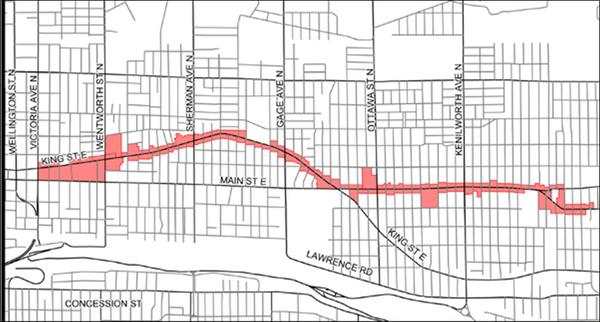

And in fact, the city is signalling a preference for the gentle end of the scale with the transit oriented development zoning that has been placed in the LRT corridor.

The transit-oriented development zoning in the eastern LRT corridor.

However, the six-storey (22 metres) height is just as likely to stimulate negotiations for more permissions than to prompt anyone to proceed "direct to site-plan", as the phrase is - a point which Vrancor has just illustrated very clearly by asking for 25 storeys on a six storey site at Queen and King already under construction ("Anger over proposed growth of two core projects", Spectator, January 27, 2020).

Parking for a six storey building, Vrancor style. South west corner King and Queen, February 2020.

A couple of detailed Canadian studies on the desirability of the Missing Middle came out last year, one from Ryerson and another from Evergreen and the Canadian Urban Institute.

However, when you read through the Missing Middle reports, it becomes clear that the Evergreen study was prompted partly by the distress of those who find themselves unable to qualify for a mortgage as they enter the family planning years; and partly by an imperative to unlock land value in so-called stable areas zoned for detached and semi-detached dwellings, whose protections threaten to impede the growth machine.

The Ryerson study, which focuses on Mississauga, points to that problem, but sets it aside in favour of looking for opportunities for denser infill mostly outside the single detached housing tracts that occupy about thirty percent of the land there. These concerns are coupled with complete reliance for remedies on the private market, whose actors are to receive various encouragements i.e have their profit margins guaranteed. Accordingly, there is nothing in this discussion as currently framed for lower income renters.

Apart from simply giving developers money, or saving them money by reducing oversight, or allowing them more floor area in return for a few below-market priced units i.e. licensing them to do outright harm by building beyond the plan which defines what is best for all, there is not much to be done to achieve affordability in the market.

Reduction in unit size is a possibility, and is ongoing. Except in jurisdictions where a minimum size is legislated, nobody knows how small a unit the market can be made to accept, and legislation is changeable. Inclusionary zoning is frequently mentioned, but apart from other problems, it cannot yield very many units.

And finally there is filtering, the process by which newer builds presumably drive down the prices that can be charged by the owners of older builds. But filtering is very dependent on local conditions and in any case takes years to moderate values, years which may pass pleasantly for the generally comfortably housed advocates of filtering, but less pleasantly for the poorly housed who are waiting to inherit.

In short, there is no market solution.

The technical route to housing affordability is probably through energy-efficient building on off-market land with ready access to public transit. I say "probably" because the practicability of any particular solution has not been adequately studied in the local conditions. It has not been a goal to plan for true and lasting housing security, and this is a political, not a technical problem.

The immediate political problem is to ensure that the land which Metrolinx has now aggregated from a large number of small-holdings is kept intact, and to have the parcel transferred to a public body or a trust, rather than breaking it up and selling it off to individual private developers, which will have the effect of worsening the housing crisis. For the sake of variety of course it might be desirable to lease land to a number of proponents, but long-term affordability depends on retaining the entire parcel in public hands and off the market in perpetuity.

The new owner would begin by rehabilitating the existing vacant buildings, completing deep energy retrofits where possible, and then turn to building stacked townhouses or smaller apartment blocks on the vacant lots, in order to make the new units available quickly.

How this could be done would not be hard to find. The literature is extensive and there is local experience of building to meet passive house standards of energy conservation. The technical problem reduces to establishing the minimum initial cash investment that would be required to get started, and identifying a lender or guarantor, probably the federal government.

Both the Liberals and the Conservatives would tacitly resist limiting opportunities for the employment of private capital by taking land off the market, no matter what the public rhetoric they might spout, but a discussion of the political task that this entails is a topic for another day.

But why should a stock of affordable housing be developed, and for whom? Or better, why is it more costly in the long run not to develop such a stock? Who would we want to attract with this housing? Not priced-out young professionals or property speculators from Toronto, nor retired persons looking for a way to stretch their fixed means, though the first and the last should of course be welcomed and not condemned for their inadvertent individual contributions to what are structural problems.

But these people are not enough to give us a future as anything other than a dormitory suburb of Toronto really. Surely we still have more self-respect than to settle for that. No, we need the housing not only to provide a floor for people already here, so they can begin to climb out of a poverty pit that has become a funnel with an ever steepening slope, but equally importantly, to attract new immigrants from everywhere, to retain new graduates from Mac and Mohawk, and to draw and keep artists and musicians - all of whom will need a place to live which they can afford.

Without these kinds of people, stagnation and decline are inevitable, no matter how promising it may seem in the short run to import a batch of computech jobs with workies attached from Toronto. The centres of decision will be elsewhere, and the interests of Hamiltonians will be readily sacrificed.

Because we are not reproducing at the replacement rate, and because the Canadian state participates in American wars for control of strategic resources that produce great disruption and loss of life, we need to bring in voluntary immigrants and refugees. And they would benefit themselves as well as us by coming in because many would have greater physical security, and may be able to send some earnings home.

They will not do as well as rapidly as those who came before, but that is of no matter to those who determine Canadian immigration policy. They are holding the gate open because they want the children of those immigrants.

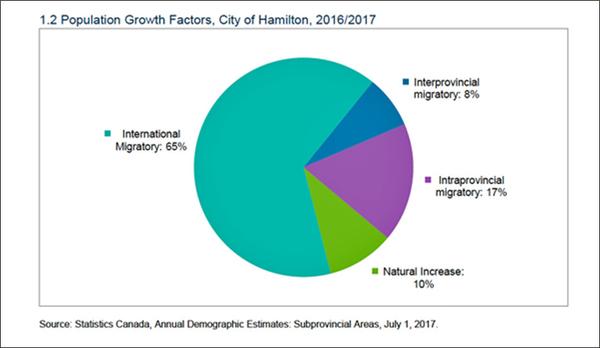

The City of Hamilton's population growth is approximately 1% per year. In 2016-2017, almost two-thirds of that was attributable to immigrants, who numbered about 3700. Source: A Demographic Profile of Immigrants in Hamilton, Hamilton Immigration Partnership Council, March, 2019.

The chart above is from a statistical compilation which tells us, among many other interesting things about the languages and ethnic origins of incoming Canadians, that

Among all immigrant and non-immigrant groups, the annual income of females was lower than males.

Length of time in Canada correlates with higher income, indicating that incomes rise as immigrants become established, yet overall immigrants have not reached parity with non-immigrants in terms of income. Across all immigrant arrival periods, those who came to Canada prior to 1981 had the lowest rates of low income (10%), even lower than non-immigrants (13.8%).

Among recent immigrants living in Hamilton in 2016, 35.2% had a university certificate, diploma or degree at the bachelor level or above. Recent immigrants had significantly lower earnings than both immigrants and non-immigrants across all educational levels, and their low-income rate (43.0%) was almost three times higher than the population overall (15.3%). We need to settle these people here, but where are they to live when they first arrive?

We need also to retain some portion of the students who graduate every year from McMaster and Mohawk. The McMaster undergraduate student body is about twenty-seven thousand strong these days. Alongside them are about 5,000 graduate students in masters and doctoral programmes. Each year the university confers seven thousand degrees, five thousand of which are Bachelors of Arts, Sciences or Engineering.

We would like to settle some of these individuals here, but again, where are they to live? Where is the affordable rental housing for young people just beginning their careers and earning comparatively little, whatever their potential may be? Finally, there are the members of that "flourishing local arts community" whose existence McMaster flacks feel important to mention on the university's brochure page. These individuals have been coming from other parts of Ontario, chiefly Toronto, but also from abroad.

Artists and musicians are the voluntary portion of low income earners, if I can put it that way. These are people who are often highly educated and therefore economically mobile if they wish, but who feel, rightly or wrongly, a vocation and are prepared to act on that conviction. They are not excluded, they choose a special form of participation: life in the art world, which is either a decadent playground for permanent adolescents or an anticipation of a utopia of non-alienating work, depending on who's judging.

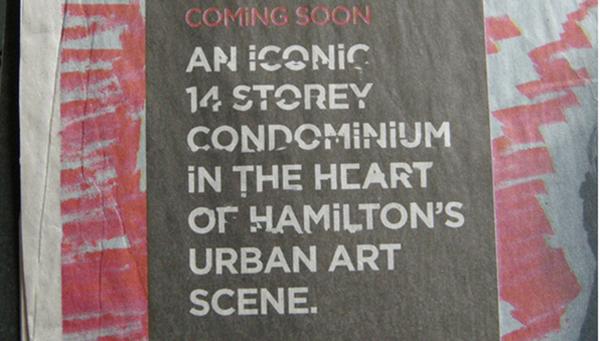

They provide some of us with temporary relief from the posturing and pettiness at City Hall, the callousness of the REITs and the ugliness and wastefulness of much of the new product that the developers bring to market. For others, artists are the "footsoldiers of gentrification", scorned for their pretensions, their aloof abstraction from the bread and butter concerns of the rest of us, and their apparent acquiescence in the condo-ism of the city's ecdev crew and the marketing slogans of the developers.

In conversation many artists are well aware of their ambiguous position in the local economy, and of their mostly unsought role in the "urbanist" spectacle of real estate promotion. As a group they are as divided as the rest of the city.

Advertisement for an off-King new build.

How much the arts amenity actually influences locational choice is not very clear. It certainly gets lots of lip service, but is this anything more than publicists both private and public recycling each others boiler plate? The other week a real live entrepreneur and business owner was invoking the familiar city-building rubrics - at least, according to publicists KGA, who had him saying in a press release that

"Hamilton offers all the right elements for our employees. It's affordable, has fantastic restaurants, vibrant nightlife, a great arts scene, and offers active green space nearby. It's also within close proximity to our headquarters in Toronto, providing easy knowledge-sharing across both offices."

The speaker was Darrel Heaps, founder and CEO of Q4, on the occasion of the announcement that his firm had leased premises at 59 King East (a Core Urban holding) and would be engaging up to 140 bright young things to frolic in the wellness room, the games room, and the outdoor patio, as well as to savour the cuisine on King William and vicinity - much of which is also owned by Core Urban.

The real draw for Q4 and similar outfits is the chance to retain employees longer while paying them less, because as city staffer Judy Lam told the Spec, "For the first time, some of their employees will be able to start a family and afford a house or condo to live in." (Hamilton Spectator, 21 January 2020.)

Whatever the importance of the "art scene" may be, city councillors certainly do not act as if they believe any of the publicity about arts-related "vibrancy" helping to induce investment. True, there is language in the new downtown secondary plan to the effect that proposed residential development close to an existing live music venue must be built with noise attenuating measures (so the new residents don't start campaigning against the venue) but the destroyer of Toronto's live music scene is not neighbour complaint but rocketing land values.

There is no talk at city hall of any provision to make a special tax class as Toronto was able to arrange with the province when it seemed that 401 Richmond, a commercial rental building occupied mostly by arts organizations, was headed for forced shutdown. The problem was that assessment based on "highest and best use" of the land, e.g. a condo tower, was yielding a tax bill in excess of the tenants' means. The solution was the establishment of a new property tax class for Creative Co-Location Facilities, with the rate set by the city, and the drafting of a set of criteria for inclusion in the new class.

Again, as with the other lower income groups discussed above, housing affordability is the chief difficulty facing artists and musicians in Hamilton. It doesn't much matter if venues survive and studio space is attainable, if you can't find a place to live anyway.

No Big Money coming in? Little Money providing shelter, food, drinks, eternal beauty and well being, and coffee on King. There's also a corner variety store.

Almost every large city is a global city now, inhabited by people with nested identities. And many of the inhabitants of cities in the hinterland of a metropolis are undergoing the same impoverishment by a rentier class who own more and more and produce, well, nothing really. It is suicidal to allow still more land to pass into the possession of this vampiric class, unless you are a revolutionary or an authoritarian reactionary, in which case everything is developing just fine.

Rise of the residential REITS. Source: Martine August, 'Canada's Rental Housing Goldmine: The financialization of multi-family rental apartments', 2017.

For an account of the growth of one of these outfits from rooming house owner to billion dollar operation, see last year's article from the Hamilton Tenants Solidarity Network on this site. The trusts, whose business model is essentially to bleed lower and middle income earners and send some of the money on to their middle and higher income shareholders, are now being joined in the Canadian market by giant private equity firms. (Tim Kiladze, "The rental rush", Globe and Mail, November 30, 2019.)

In a 2015 article for the "The Journal of Urban Affairs" Gillad Rosen and Alan Walks draw the outline of the current mechanism of "city building", in which financialization has replaced industrialization as the driver of capital flows, and explore what this has produced in Toronto.

Third-wave urbanization has likewise involved a spatial shift from suburbanization and urban dispersion toward concentration, gentrification, and intensification, which bring with them profound changes in urban social life. We argue that in cities like Toronto such shifts are tightly intertwined with the rise of what we term condo-ism. The latter refers to a particular mode of development rooted in a nexus of, on the one hand the economic interests of the private sector development industry and the state, and on the other new urbane yet privatized residential preferences, lifestyles, and consumption interests among consumers. This has resulted in a new structured coherence of political and economic interests... dependent upon continued intensification and real estate development in the city, with mortgage credit displacing industrial expansion as the primary driver of the urban growth machine. In the context of financialization and globalization, condo-ism has thus usurped the role of industrialization in urban development. Toronto is an exemplar of this process. (Rosen and Walks, "Castles in Toronto's Sky")

Renters have the most difficulties under this regime, and not only lower income renters but those of middle income as well, as is evident from the fact that both have been coming here for some years seeking relief. This would seem to imply the possibility of a broader coalition directed at a non-market solution, but somehow this seems not to occur to the struggling children of the lower middle classes - probably because they are so alarmed by the unexpected prospect of downward mobility that all their efforts are aimed at grabbing a rung on the home-ownership ladder. The odds against them are lengthening.

Hamilton, November 2019, first snow. With permission.

I'll give the second last word to City of Hamilton planning staff, who after all are the experts in these matters.

The Downtown Secondary Plan contains this stirring affirmation:

6.1.3.7 Diversity of Housing Housing is fundamental to the economic, social, and physical well-being of Downtown's residents and neighbourhoods. Housing is a basic human need and is the central place from which people build their lives, nurture their families and themselves, and engage in their communities. Downtown's livability and prosperity is connected to the provision of housing that meets the requirements of a diverse population with varying housing needs. Downtown offers various built form housing options, including grade-related, mid-rise, and tall buildings with a variety of ownership and tenancy. Providing housing to a wide range of residents that is affordable, secure, of an appropriate size, and located to meet the needs of people throughout their life is the goal of an inclusive Downtown and essential to the creation of complete communities.

Fine words. Surely this is intended as a manifesto, a statement of principle which ought to be endorsed, but in fact is silently rejected, by city council, the chamber of commerce, the developers and their architects and lawyers, the leadership of the construction trades, LIUNA, the health care principalities, and the strategists of all three major political parties.

In fact, almost nobody but tenants in rental housing and the homeless in their camps actually feels the need for their right to housing to be met - affordable, secure, adequately sized and located housing, that is. Everybody else thinks it is somebody else's responsibility. Or no-one's.

Meanwhile those buildings all along King Street East are sitting there, intact and empty, and the next logical step is obvious to all. Whether anyone will take it remains to be seen.

Main near Ottawa, January 2020.

You must be logged in to comment.

There are no upcoming events right now.

Why not post one?